Image & conflict

The History of the Yellow Vests By Us, a 1 hour 42 minute film (available HERE), recounts one year of transformation of the yellow vest movement from November 17th, 2018, to November 17th, 2019, from its first day to its first anniversary. In a chronological format, in four chapters, it covers different aspects of the movement: the struggle against political representatives, the 2,000 roadblocks and the dynamics of evictions/reoccupations, direct actions and centralized demonstrations, the defense of a common position in the face of justice, the care of the wounded and prisoners, autonomous walkouts in factories, and the movement’s general inability to attack the organization of work as a whole. What interests us in this article are specifically the international echoes that resurface throughout the one-year chronology of the Gilets Jaunes.

The international theme appears four times, we would like to explore the distinction between the first international sequence (November 2018/January 2019) and the last (August/November 2019). We are convinced that the simultaneous uprisings in a dozen countries (August/November 2019) represent a real qualitative leap that took place in the summer and fall of 2019, on an international scale, in which the future of the Gilets Jaunes movement was at stake.

It is necessary to deepen the political meaning of these two sequences by distinguishing the image of the struggle from its actual content. An image spreads faster than a conflict. That is why our role is not to share visuals but to interpret them in the context of class conflict. From this perspective, the international dimension is not secondary: it is essential if we are concerned with the question of revolution.

In the first sequence, the vest becomes a transnational symbol onto which everyone projects their way of making their demands visible. However, in the last sequence, it is not the “contagion” of the image that is emphasized, but the intensification of links and exchanges between movements taking place simultaneously in different countries. While at the beginning the international situations were simply an appropriation/projection of the image of the Gilets Jaunes, by the end this image has been completely overtaken. The vest, which initially symbolized a national protest, now seeks, in the real content of internationalstruggles, the means to expand, to transcend its own limits as well as those of the other movements that inspire it.

These movements did not appear simultaneously due to some mystical alignment of three planets in 2019, but because the global economy is based everywhere on the same principle: the exploitation of one class. The struggle can only emerge with snowballing. It has to start somewhere, and it is not a question of claiming that it all began with the Gilets Jaunes, from a self-centered or nationalist perspective. What needs to be affirmed is that all these struggles are connected because they are structured by common social conditions, in a same period of crisis of global capitalism.

There is never a single explanatory thread, but the same causes can produce the same effects. During the Yellow Vests movement, we didn’t have time to understand the difference between the uprisings in Guinea and Catalonia… We didn’t have time to understand the unique characteristics of international uprisings, but we did have time to feel their energy.

A movement isits ability to be joined. A movement can be joined because it is talked about and debated, translated and propagated. Distant struggles and uprisings elsewhere can amplify the global joinability of movements. They constantly feed into their continuity, active memory, and the conditions for the resurgence of new conditions of joinability.

The wake of a movement is a beginning, a breach that can open the way. How many times have we heard the phrase ? “When things really kick off, I’ll be there!” This phrase really applies.

November 2018 – January 2019

First, let’s analyze the first sequence of the film, which deals with internationalisation.

“While Burkina Faso, Sudan, and Zimbabwe protest against fuel costs without the yellow vest symbol, in Iraq a new wave of anti-corruption protests adopts the yellow vest symbol to revive their struggle.”

“As during the Arab Spring in 2011, protests are breaking out in clusters. Activists are imitating each other. They are responding to the same overlapping societal problems around the world… The real reason for the movement is social injustice, and this is truly global.“

The narration lists about fifteen countries and shows 25 images of international protesters waving yellow vests.

***video excerpt to be added***

In Taiwan, a reformist organization fighting for tax justice has adopted the colors to take to the streets.

In Pakistan, it is a tool for sectoral visibility, worn by striking engineers demanding higher wages.

In Morocco, it is worn by shopkeepers and taxi drivers protesting against a reform.

In Portugal, as in Belgium, on the internet people call to block roads and cities and protest against taxes and the high cost of living.

In Ireland, the yellow vest crystallizes social anger over the housing crisis.

In Greece and Lebanon, the yellow vest evokes post crisis austerity.

In Iraq, they protest for public services and against the political corruption that diverts funds from them.

In Israel, Bulgaria, Romania, the Netherlands, Hungary, the United States, Poland, and Serbia, the yellow vests protest against the concentration of power, the erosion of democratic rights, the decline of justice, and authoritarian abuses.

In Serbia, Slovenia, and Croatia, the yellow vest is worn by young people, the media reports the cause as social decline and exclusion from the labor market.

In Canada, the yellow vest is used in protests against carbon taxes, but also against immigration, suggesting a possible shift to the far right for the symbol, which is echoed in Australia, Germany, France, and probably elsewhere.

In Italy, it has been taken up by both nationalists protesting against taxes and opponents of migration policies.

While pro-Brexit protesters burn European Union flags in front of parliament, the left wears vests for a march against the conservatives austerity policies.

In Tunisia, the arrest of a man in possession of 50,000 yellow vests reveals the latent power of a symbol capable of foreshadowing a revolt even before it takes shape.

In Egypt, the state banned its sale even before protests emerged, for fear of imitation. Visibility is a threat. The yellow vest thus becomes a specter: what it could have represented is enough to justify its repression.

There is no political coordination. The vest has the advantage of being easy to wear. You just have to put it on to join in.

It is a historic moment in which workers from around the world share the same anger at the crisis of capitalism, but project it according to national or sectoral subjectivities.

Immediately recognizable, the vest becomes an easy-to-wear global symbol, a transferable image spreading faster than the conflict itself. However, it is not the image of the movement that we should seek to spread, but its content/class conflict.

We can talk about a form of contagion, but one that is less significant in qualitative terms than the developments that will follow.

February 2019

The Gj movement synchronizes with numerous international events, particularly in Algeria and Haiti.

In Haiti and Algeria, massive demonstrations break out against Presidents Jovenel Moïse and Bouteflika. These two movements have turned into widespread rejection of the political regimes in place. With no major political parties at the head of these movements, people are organizing via social media and outside the traditional frameworks of unions and parties.

Between Algeria and France, there is shared recognition within the movements, placards circulating links, speeches at demonstrations, and posts on social media.

“Macron supports Bouteflika, Algerians support the Yellow Vests!” (Slogan from a demonstration in Paris in February 2019)

“We learn that repression is an economy; the weapons used against us are sold abroad and even to formerly colonized countries… the repression of struggles is part of a global security business. “

In this second phase of internationalization, the same weapons are used to repress us elsewhere. In the struggle against states, the Gilets Jaunes arise international consciousness. The synchrony of these three uprisings, initially protesting against the corruption of a bourgeois faction in power, contribute to the insistent tendency of movements to attack the entire system.

JULY 2019 – NOVEMBER 2019

***video excerpt to be added***

Finally, we come to the third international sequence, from summer 2019 to October/November 2019. There is an escalation of uprisings that the film chronologically exposes, up to November 15, 2019 in Iran. The film does not mention Colombia, which rises up on November 19th, 2019, because the film ends on November 17th, 2019, on the anniversary of the Yellow Vests.

In various contexts: Hong Kong, Indonesia, Chile, Iraq, Ecuador, Bolivia, Iran, Catalonia, Lebanon, Guinea, Colombia. The density of events in such a short period of time raises the question of a cycle of struggles in the sense that there is an accumulation of experiences, tactics, and mutual recognition of the uprisings as moments of a same historical sequence.

August 2019

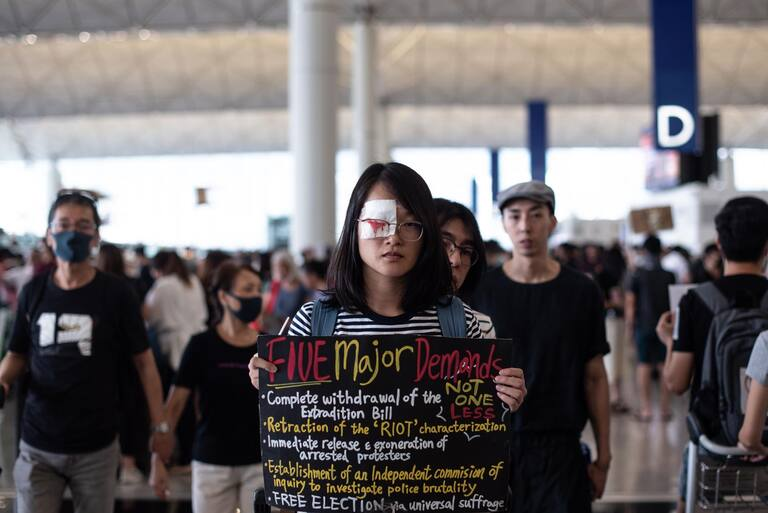

In Hong Kong, the two months of university occupation and the occupation of the international airport on August 12th attracts global attention. University students, precarious workers, taxi drivers, and teachers join in the outrage against extradition, but also in the uprising that goes beyond its initial demand.

In Indonesia, on August 19th/21st, racist violence and arrests of Papuan students led to riots. Public buildings are set on fire in Manokwari and Jayapura.

The causes that triggered the struggle are different: the fight against extradition and the Chinese state in Hong Kong and against state colonial racism in Indonesia. But from the Gilets Jaunes movement’s point of view, the echo which reaches us is the use of Hong Kong’s “Be water” tactics to circumvent Indonesian security controls.

A second wave emerged in Indonesia from September 23th to 30th, with massive mobilization against a series of repressive laws: the weakening of the anti-corruption commission and the strengthening of Islamic criminal law. As in Hong Kong, universities are occupied and there are clashes with the police in Jakarta, Bandung, and Medan. Students are shot and killed…

At the fourth Assembly of assemblies of the Yellow Vests, held in Montpellier, a committee of around forty Gilets Jaunes write an appeal to place the yellow vest movement within a broader context, referring to it as a “planetery uprising.”

In Hong Kong, in September, weekly clashes continue, shopping malls are occupied. There are technical developments in the organization without leading processions, with the evolution line coordination practices of different specializations: skouts, frontliners, stone throwers, medics, magicians…

September 2019

In France, on September 21st, during the Act 45 (45th week) of the Gilets Jaunes in Paris, six different starting points for demonstrations compete with each other. The catchword is “Be water.” The strategy involves removing the vest and putting it back on after passing a police units, or dressing in black and carrying several changes of clothes.

These days, protesters wearing vests are heavily repressed with fines of €135.

“In a confusing atmosphere, while some are calling for the vest to be removed to avoid fines, others are calling for it to be removed to pass themselves off as good citizens. “

One might think that removing the vest would make the movement more universal, more accessible, but this removal causes us to lose power. Removing the vest opens the door to the usual political recuperation because the symbol of the vest concentrates the negation of all historical trajectories of recuperation and integration of movements into the state.

Becoming international, yes. Diluting ourselves in a recuperative form of citizenship, no. Protesters in France who offer the negation of the vest as a symbol of unity weaken the true scope of the movement.

October 2019

On October 1st, in Iraq, the anti-corruption movement resurfaces. The crackdown is immediate: snipers, internet shutdowns. In a few days, more than 100 people are killed. This time, the protesters do not wear vests, but they are much more numerous.

From October 3rd to 13th, in Ecuador, an agreement with the IMF leads to the removal of fuel subsidies, doubling the price of diesel. Students and indigenous organizations join the national transport strike. Three oil fields are occupied and roads blocked in several regions.

In Hong Kong, on October 13th, protesters wave Catalan flags to express their solidarity with the Catalan movement.

In Catalonia, on October 17th/20th, slogans of support for Chileans were chanted at demonstrations.

In France, banners at the front of marches continue to mention the struggles in Hong Kong, Iraq, Chile, and elsewhere.

The appropriation of umbrellas in national calls to action in Nantes and Montpellier anchor the movements desire to appropriate the world moment set of skills. The technique of using traffic cones to stifle tear gas is often mentioned in Gilets Jaunes organizing spaces.

In Lebanon, on October 19th, the slogan “A revolution throughout the Arab world!” appears.

On October 14th, in Catalonia, a large demonstrations break out after the conviction of independence militant leaders. Barcelona airport is occupied, as in Hong Kong and Indonesia. Violent clashes in Barcelona, street fires, barricades, without a specialized front line, all the participants in the demonstration overflow everywhere, participating with “line coordination” as in Hong Kong. The independence movement is primarily nationalist, but the practices of confrontation and occupation createsnew links between precarious youth, students, workers, and anarchist militants.

On October 17th, in Lebanon, after the announcement of a tax on the WhatsApp application, massive demonstrations take place throughout the country. Roads are blocked and squares occupied.

On October 18th, in Chile, young people began by jumping over subway gates. Then they burn down stations. The initial protest is against ticket prices but immediately encompasses the entire system and history of accumulated injustice. Santiago is paralyzed, and a “state of emergency” is declared. The army is deployed in the streets.

From October 1st to 18th, in Iraq, Catalonia, Lebanon, and Chile, events unfold rapidly. Four uprisings begin in less than three weeks, with airport occupations, blockades, sabotage, and fires, all targeting symbols of the state and vital infrastructure, transportation, communications, and city centers.

The use of lasers to thwart video surveillance and destabilize the cops spread from Hong Kong to Chile, Lebanon, and Iraq.

While the Gilets Jaunes occupation of roundabouts is becoming increasingly marginalized, in Iraq, in Baghdad, the Tahrir Square becomes a self-managed camp, with infirmaries, collective kitchens, libraries, art workshops, and popular councils. In Chile, territorial assemblies are self-organized assemblies that are set up in neighborhoods and villages.

Compared to the 2011 movement, the 2019 sequence is more dynamic; people are not occupying to sit around and experiment with forms of direct democracy that reduce the movement to passive/static states. They are occupying to organize, to sort through the practices of confrontation on the basis of effectiveness and attention, they are sharing information and collectively assessing the balance of power. What are we attacking and how do we continue?

November 2019

In Guinea, protests against President Condé’s third term are take place on a weekly basis, similar to the Gilets Jaunes, one protest per week rhythm. As in Algeria and Haiti a few months earlier, the issue goes beyond the personalization of power and concerns the entire political system.

From November 15th to 20th, in Iran, following a sharp rise in gasoline prices, hundreds of towns and villages rise up within a matter of hours. As in Ecuador, energy infrastructure are blocked, but in Iran the clashes are much more violent. With the internet cut off, no information comes out of the country.

In Colombia, on November 21st, a national strike against neoliberal reforms is inspired by the same slogans as in Chile. There are scenes of rioting in Bogota and barricades in the suburbs. On November 23rd, Colombia became the fifth country to use lasers against surveillance drones.

In Colombia, the Chilean slogan “Chile despertó!” (Chile wake up!) is adapted to “South America, wake up!” Bolivian flags are waved and protesters talk about the situation in Ecuador. On Colombian social media, messages of support circulate in support of Iranian protesters, as they learn that 400 people have been brutally killed by the Iranian state during the internet blackout of recent days.

7 are killed in Ecuador. X in Guinea. X in Colombia. 36 dead in Chile. 13 in Indonesia, 23 in Bolivia! State dogs fire live ammunition in Iraq and Iran, 105 killed in Iraq, 400 or 500 killed in Iran.

There are thousands of wounded, including 24 mutilated in France, in Chile, 427 blinded by riot rifle fire, rubber and hornet grenades, and other weapons such as tear gas bombs! The gouged-out eye symbol of police repression is appropriated by the uprisings in Hong Kong, Chile and France.

Thousands of arrests in each uprising are accompanied by prolonged judicial violence, Hong Kong militants declared missing…

All these uprisings are met with state repression. This theme is widely taken up by the left in various countries, who use this violence to challenge the powers in place by offering to reform them. But we cannot be content with the status of victims, much less with reformism. We need a union not based on shared powerlessness in the face of repression, but based on class autonomy practices to face it.

Class consciousness is born in conflict. What we are trying to do by creating shared narratives of uprisings is to show how each event is an update of the previous one, a place to return to and revive the recipes for future events.

We block a road without permission, we light a barricade. We realize that there are many of us. We talk, we eat, we organize to hold out. We talk about autonomy, insurrection, tactics, revolution. We don’t come from the same place, but we find ourselves at the same point. The struggle makes it possible to rewrite our affiliations; we are no longer individuals subject to government policy, we are together against those who prevent revolution.

In France, the Yellow Vests did not initially identify with any particular class. But on the roundabouts, in diversity, we defended the unity of the movement and laid the foundations of a revolutionary subject.

Where are we in the cycle?

Uprisings follow discontinuous timelines, marked by phases of growth, stagnation, and contraction: prolonged occupations, brief insurrections, successive waves.

In France, the Yellow Vests movement peaked after three weeks but lasted for over a year. The situation is similar in Chile, where the October 2019 uprising paralyzed the country for several weeks but subsided after the promise of a new constitution. In Hong Kong, the rise is slow but maintains a constant intensity thanks to tactical mobility. In Iran, repression crushed the uprising in four days, only for it to resurface with force in 2022.

Despite defeats or repression, the movement returns, sometimes weeks, months, or years later. This can be seen in Indonesia with two consecutive waves of mobilization, or in Bolivia with an uprising divided between protests against Morales and then against the coup.

Since 2015, Lebanon and Iraq have experienced major mobilizations every 12th to 20th months, almost simultaneously. Each mobilization shapes the next, with multiple triggering events, explosions, economic crises, tragedies, victories… The resurgence lives of memories of past local struggles combined with collective international tactical learning.

This pattern is also repeated in France, Chile, Indonesia, Haiti, and Sudan. The return of waves is stimulated by neighboring revolts, in transnational resonance. Collectively, we are approaching a moment where many people in many places are thinking the same thing at the same time: not why a movement fails, but when will it return.

For us, the question is: where are we in the cycle? This means asking ourselves: where are the forces of the movement? How can we overcome separation by looking at how and whateach sequence of struggle says about a broader historical moment?